Late in 1877 adventuresome prospector Ed Schieffelin (1847-1897) left the safety of Fort Huachuca to look for silver in the hills on the east side of the San Pedro River in southeastern Arizona. Rich ore had been found there 20 years before, but the US Army had only recently tried to take the San Pedro Valley away from militant Apaches. You’ll not find your fortune out there, the soldiers told Schieffelin, only your tombstone. Within weeks he found both, facetiously naming one of his silver strikes the Tombstone Mine and the other the Graveyard Mine. Early the following year Schieffelin returned with his brother Al and partner Richard Gird (1836-1910) to discover the Lucky Cuss and the Tough Nut.

Prospectors, miners and speculators quickly followed and the town of Tombstone, named after the mining district, was surveyed in December 1878. The territorial governor showed up early in 1879 and invested in a processing mill on the San Pedro River. In May 1879 the population was estimated at 250. By the end of that year, Tombstone had become the most famous boomtown in the West, incorporated as a village, with a population just under a thousand, having a newspaper, and a post office for nearly a year already. Saloons made more headlines but four churches had been organized by 1880. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church (1882) survives as the oldest Episcopal building in Arizona. It was built under the leadership of the well-known Reverend Endicott Peabody (1857-1944).

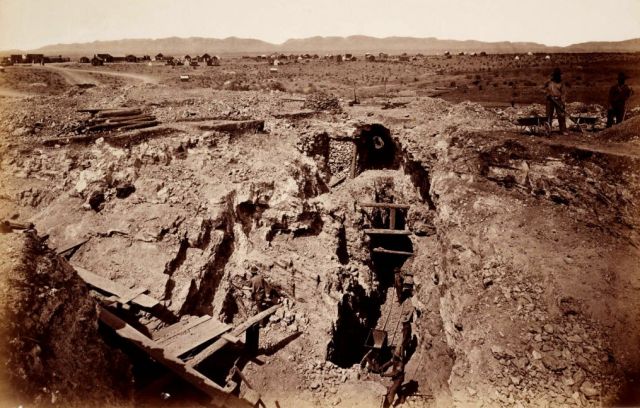

The noted stereograph photographer Carleton Watkins (1829-1916) brought his camera to Tombstone in April 1880, recording this view of the old south shaft ore quarry at the Tough Nut Mine. The eastern quarter of Tombstone, laid out on Goose Flat, is visible across Toughnut Gulch with the Dragoon Mountains behind. Most of the town is out of view at left including an already prosperous business district. There were 110 industrious Chinese residents in Tombstone in 1880, many of them self-reliant entrepreneurs. (From a glass plate at Yale Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.)

The noted stereograph photographer Carleton Watkins (1829-1916) brought his camera to Tombstone in April 1880, recording this view of the old south shaft ore quarry at the Tough Nut Mine. The eastern quarter of Tombstone, laid out on Goose Flat, is visible across Toughnut Gulch with the Dragoon Mountains behind. Most of the town is out of view at left including an already prosperous business district. There were 110 industrious Chinese residents in Tombstone in 1880, many of them self-reliant entrepreneurs. (From a glass plate at Yale Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.)

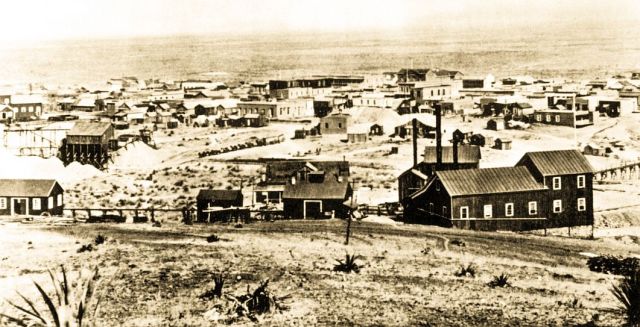

This birds-eye view of Tombstone in 1881 shows an ore wagon pulled by 15 or 16 mules leaving town for one of the mines or on the way to a mill. The town had a population of about 4,000 that year with 600 dwellings and two church buildings. There were 650 men working in the nearby mines. The Tough Nut hoisting works are in the right foreground. The firehouse is behind the ore wagons, with the Russ House hotel just to the left of it. The dark, tall building above the Russ House is the Grand Hotel, and the top of Schieffelin Hall (1881) is visible to the right. Fire burned a large portion of the business district 22 June 1881 and then again in less than a year. The Grand Hotel opened in September 1880 and was lost in the 26 May 1882 fire. Both fires were stopped on the south side of Fremont Street, sparing the original Epitaph newspaper office, Hotel Nobles and Schieffelin Hall.

This birds-eye view of Tombstone in 1881 shows an ore wagon pulled by 15 or 16 mules leaving town for one of the mines or on the way to a mill. The town had a population of about 4,000 that year with 600 dwellings and two church buildings. There were 650 men working in the nearby mines. The Tough Nut hoisting works are in the right foreground. The firehouse is behind the ore wagons, with the Russ House hotel just to the left of it. The dark, tall building above the Russ House is the Grand Hotel, and the top of Schieffelin Hall (1881) is visible to the right. Fire burned a large portion of the business district 22 June 1881 and then again in less than a year. The Grand Hotel opened in September 1880 and was lost in the 26 May 1882 fire. Both fires were stopped on the south side of Fremont Street, sparing the original Epitaph newspaper office, Hotel Nobles and Schieffelin Hall.

Residents successfully lobbied the territorial legislature to create Cochise County 1 February 1881 with Tombstone as county seat. The population of Tombstone probably surpassed every other city in Arizona the following year, except maybe Tucson. Some estimates gave a population figure about double the count made by a territorial census: 5,300 in 1882. Of course, lots of men were always in town without being counted residents.

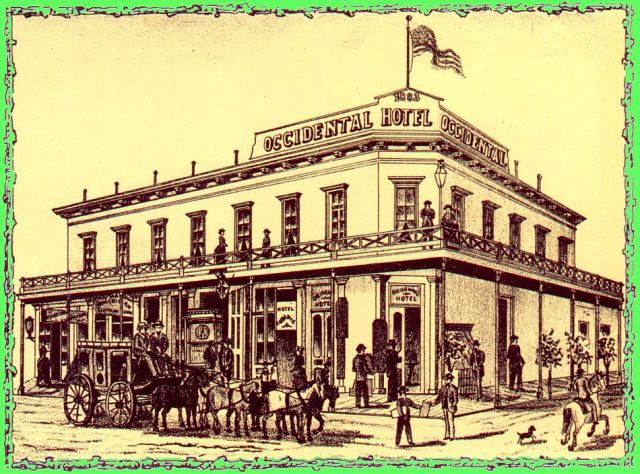

The Occidental Hotel was built on the southeast corner of Allen and Fourth Streets. Joseph Pascholy and Godfrey Tribolet were proprietors. A hundred guests could be accommodated on the European plan at rates from 50-cents to $2 a day. This illustration is from Wallace W. Elliott & Co., History of Arizona Territory. . ., (1884) as reproduced in The Image of Arizona by Andrew Wallace (1971). The building burned sometime in the 1890s.

The Occidental Hotel was built on the southeast corner of Allen and Fourth Streets. Joseph Pascholy and Godfrey Tribolet were proprietors. A hundred guests could be accommodated on the European plan at rates from 50-cents to $2 a day. This illustration is from Wallace W. Elliott & Co., History of Arizona Territory. . ., (1884) as reproduced in The Image of Arizona by Andrew Wallace (1971). The building burned sometime in the 1890s.

Access to easy money, by investing in mines, card games and brew, led to violence in an era when men felt the need to arm themselves against attacks by Apaches or stage robbers. In Pima and Cochise counties friction developed between these “investors” and “cowboys” who made their money from livestock. But telling the whole truth about the infamous gunfight at the OK Corral is problematic. Like most storied figures, there is disagreement over whether Wyatt Earp (1848-1929) was a good guy or a bad guy. The related issue, to what extent Arizona in the 19th Century was a lawless frontier, is central to any understanding of its history. This perception of a territory of renegade cowboys and Indians, whether founded on facts or not, delayed for more than a decade Arizona’s admittance to the union as a self-governing state.

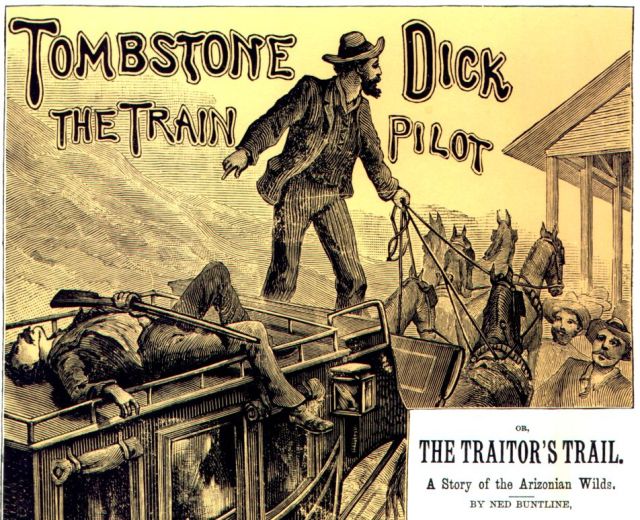

Cheap paper and printing in the 19th Century brought a flood of popular dime novels like Wild West Weekly and Buffalo Bill Weekly promoting the myth of a violent confrontation between rugged individuals in the West. This illustration is from the cover of Beadle’s in 1885. Movie scripts and then TV repeated the same legends. As Stewart Udall (1920-2010) pointed out, “Efforts by historians to put western violence in perspective encountered opposition not only from moviemakers but also from members of their own profession who glorified gunfighters as seminal figures of western history.” (p. 186, The Forgotten Founders) Stories out of three western communities more than any others fed this appetite for violence: Dodge City, Kansas; Virginia City, Nevada and Tombstone, Arizona. (Illustration from The Image of Arizona by Wallace, 1971)

Cheap paper and printing in the 19th Century brought a flood of popular dime novels like Wild West Weekly and Buffalo Bill Weekly promoting the myth of a violent confrontation between rugged individuals in the West. This illustration is from the cover of Beadle’s in 1885. Movie scripts and then TV repeated the same legends. As Stewart Udall (1920-2010) pointed out, “Efforts by historians to put western violence in perspective encountered opposition not only from moviemakers but also from members of their own profession who glorified gunfighters as seminal figures of western history.” (p. 186, The Forgotten Founders) Stories out of three western communities more than any others fed this appetite for violence: Dodge City, Kansas; Virginia City, Nevada and Tombstone, Arizona. (Illustration from The Image of Arizona by Wallace, 1971)

Wyatt Earp arrived in Tombstone before the end of 1879. He had recently left Dodge City, Kansas where he had been an off-and-on lawman. In the spring of 1880 he was a shotgun messenger on Wells Fargo stages. He was joined in Tombstone by his brothers Virgil, Warren and Morgan and Doc Holliday (1852-1887), a friend from Dodge. On 28 July 1880 Wyatt was appointed a Pima County Deputy Sheriff. Virgil (1843-1905) became a Deputy US Marshal and then Tombstone Town Marshal. Bad blood between the Earps and the Clanton and McLowery families led to a gunfight 26 October 1881 near the OK Corral. Billy Clanton (1862-1881), Frank McLowery (1848-1881) and Tom McLowery (1853-1881) were killed. Virgil Earp was wounded but not seriously. December 28 Virgil was ambushed on the streets of Tombstone and seriously wounded but he recovered, though with lasting debilities. The following March, Morgan Earp (1851-1882) was assassinated in Tombstone. The Earps and their friends put together a posse and went after their enemies in the Dragoon Mountains. In the course of a two-week ride they killed four men. Then the Earps continued into New Mexico, finally taking refuge in Colorado where the governor refused their extradition.

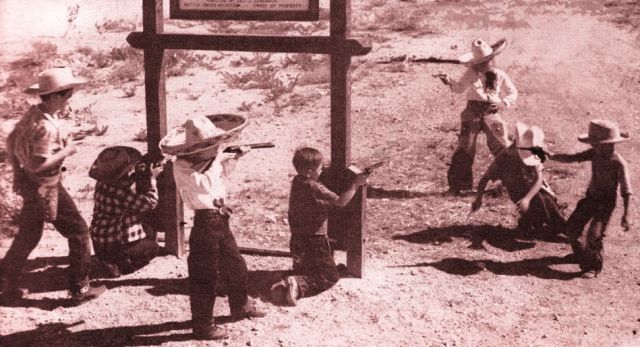

This is what the legendary town meant to several generations of young boys, and not a few men, nourished as they were on a diet of cowboy, shoot-‘em-up literature and movies. The un-named photographer staged this scene for the Tucson stock photo company Western Ways under the sign marking the OK Corral and it illustrated a September 1951 article on Tombstone in Arizona Highways magazine featuring Douglas D. Martin’s book on the Epitaph newspaper. The Tombstone Lions club undertook the restoration of the ruins of the OK Corral buildings to promote “the most furious and famous gun battle of all western history,” as the sign in this photo pointed out. At that time, George J. Geneback of Battle Creek, Michigan was owner of the property.

This is what the legendary town meant to several generations of young boys, and not a few men, nourished as they were on a diet of cowboy, shoot-‘em-up literature and movies. The un-named photographer staged this scene for the Tucson stock photo company Western Ways under the sign marking the OK Corral and it illustrated a September 1951 article on Tombstone in Arizona Highways magazine featuring Douglas D. Martin’s book on the Epitaph newspaper. The Tombstone Lions club undertook the restoration of the ruins of the OK Corral buildings to promote “the most furious and famous gun battle of all western history,” as the sign in this photo pointed out. At that time, George J. Geneback of Battle Creek, Michigan was owner of the property.

The Territory of Arizona had been largely populated by southern Democrats from New Mexico and Texas, and yet in 1880 it was led by a Republican Governor appointed by US President Chester Arthur, the sixth Republican President in a row. The US Justice Department and the Governor prosecuted a war on crime targeting “lawless” Texas cowboys and enlisted the Earps, Republicans who backed a Republican candidate for Pima County Sheriff. Following the OK Corral shooting, US Marshal for Arizona Crawley P. Dake (1836-1890) telegraphed Washington D.C. to boast how the Earps were helping rid Arizona of the criminal element. “My deputies at Tombstone have struck an effectual blow to that element, killing three out of five.”

Tombstone seemed to especially deserve its disrepute. The stage to Tombstone was held up more than once. Between October 1879 and October 1880 in Pima County there were 25 homicides followed by 15 arrests. President Arthur suggested Congress repeal the posse comitatis act secured by Democrats following the Civil War in order to limit military occupation of the south. May 3, 1882 the President proclaimed his power to declare martial law in Arizona if the violence did not abate. Then, Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected President in November 1884. At the same time, crime in Tombstone declined—along with the economy.

By 1900 Arizona newspapers had turned abruptly away from sensationalized accounts of gunfights to promote statehood for the now respectable, progressive and peaceful territory. But Tombstone saw another revenge killing at the OK Corral in 1897. And the new medium of cinema joined print stories to fill minds with legends of the Wild West. This would continue, throughout the Twentieth Century, as films and TV shows introduced new generations to lusty, rambunctious Tombstone gunfighters.

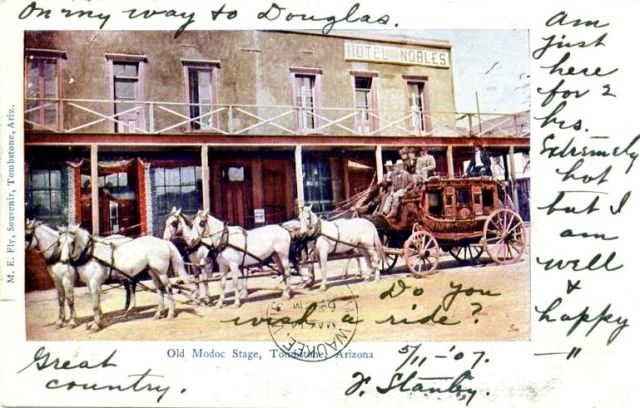

J. Stanby mailed this souvenir postcard 11 May 1907 from Tombstone and it arrived in Milwaukee three days later. “On my way to Douglas,” he wrote. “Great country. Do you wish a ride? Am just here for 2 hours. Extremely hot, but I am well and happy.” The undivided back postcard was likely issued about 1903. According to postal regulations, until 1907 correspondence had to be written on the front of the card. Only the address went on the back. Camillus S. Fly (1849-1901) opened a photographic studio behind his boarding house on Fremont Street in September 1880. The OK Corral gunfight took place in a vacant lot on the west side of the Fly Gallery. Camillus’ wife, Mary E. “Mollie” Fly (1847-1925) was also a photographer and ran the Gallery pretty much on her own from 1886 until her retirement in 1912. For this postcard she colorized one of her husband’s photos from the 1880s. The stagecoach was built in Tombstone as a large capacity “Modoc” design. After the railroad came, the old Modoc and Ben Cook coaches may have offered rides for tourists, who experienced a mock holdup along the route. In December 1925 the Modoc was donated to the Arizona Museum Society at Prescott. It was driven in rodeo parades until it became a display at the Sharlot Hall Museum. Tombstone’s Ben Cook stage is at the Arizona Historical Society in Tucson. By rail in 1907, Tombstone was a short side trip on the way from Benson to Douglas.

J. Stanby mailed this souvenir postcard 11 May 1907 from Tombstone and it arrived in Milwaukee three days later. “On my way to Douglas,” he wrote. “Great country. Do you wish a ride? Am just here for 2 hours. Extremely hot, but I am well and happy.” The undivided back postcard was likely issued about 1903. According to postal regulations, until 1907 correspondence had to be written on the front of the card. Only the address went on the back. Camillus S. Fly (1849-1901) opened a photographic studio behind his boarding house on Fremont Street in September 1880. The OK Corral gunfight took place in a vacant lot on the west side of the Fly Gallery. Camillus’ wife, Mary E. “Mollie” Fly (1847-1925) was also a photographer and ran the Gallery pretty much on her own from 1886 until her retirement in 1912. For this postcard she colorized one of her husband’s photos from the 1880s. The stagecoach was built in Tombstone as a large capacity “Modoc” design. After the railroad came, the old Modoc and Ben Cook coaches may have offered rides for tourists, who experienced a mock holdup along the route. In December 1925 the Modoc was donated to the Arizona Museum Society at Prescott. It was driven in rodeo parades until it became a display at the Sharlot Hall Museum. Tombstone’s Ben Cook stage is at the Arizona Historical Society in Tucson. By rail in 1907, Tombstone was a short side trip on the way from Benson to Douglas.

“In the last six years the County has been entirely redeemed from the wild reputation it before bore as a region terrorized by Apaches and equally wild cowboys,” wrote Arizona Territory Commissioner of Immigration John A. Black in his 1890 profile of Cochise County. “The petulant pop of the pistol is no longer heard, and, while the excitement of the boom days of yore may be missed, while the spice of frontier life may be largely lacking, there remains the solid enterprise and the substantial progress that marks the thrifty community and invites with assurance the immigrant.” In reality, economic recession and difficulty underground lay ahead.

Water began entering the 500-foot level of the Sulphuret Mine in March 1881. A year later, ore extraction had to be suspended in the big Contention and Grand Central mines while pumps were installed. When digging resumed each increase in depth was met by an increase in water. Financial panic hit Tombstone in 1884, then, fire destroyed the Grand Central pumps in 1886. The boom was over. Succeeding years would bring bigger pumps and more water as mining was reduced to a struggle between the falling price of silver and the rising cost of pumping water.

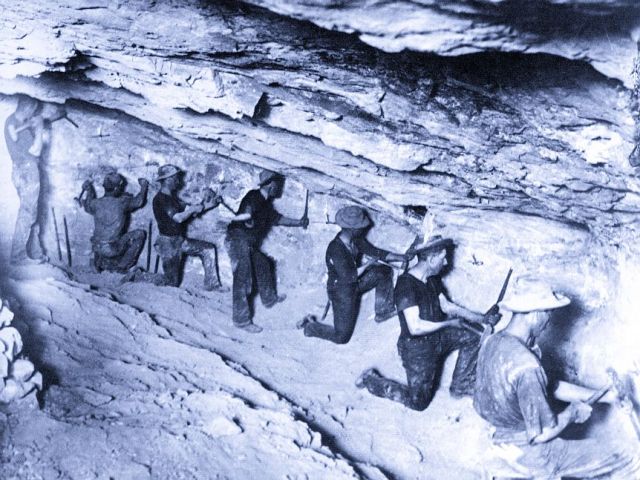

Following years of recession and closure of the mines Tombstone’s population had sunk to 646 people according to the 1900 census. Early production figures are not accurate, but it appears that Tombstone mines produced more than $19 million dollars of total value from 1879 through 1886. Following the loss of pumps, mines still averaged around a half million dollars a year for the next ten years and $4.5 million from 1897-1907. The Tombstone Consolidated Mines Company was formed in 1901, new pumps installed and mining continued below 1,000 feet. Magnesium flash powder made possible this photo taken in 1905 on the 500-foot level in the Sulphate Stope of the Consolidated mine. It shows laborious hand drilling of holes for blasting with the only light coming from candleholders spiked in the wall.

Following years of recession and closure of the mines Tombstone’s population had sunk to 646 people according to the 1900 census. Early production figures are not accurate, but it appears that Tombstone mines produced more than $19 million dollars of total value from 1879 through 1886. Following the loss of pumps, mines still averaged around a half million dollars a year for the next ten years and $4.5 million from 1897-1907. The Tombstone Consolidated Mines Company was formed in 1901, new pumps installed and mining continued below 1,000 feet. Magnesium flash powder made possible this photo taken in 1905 on the 500-foot level in the Sulphate Stope of the Consolidated mine. It shows laborious hand drilling of holes for blasting with the only light coming from candleholders spiked in the wall.

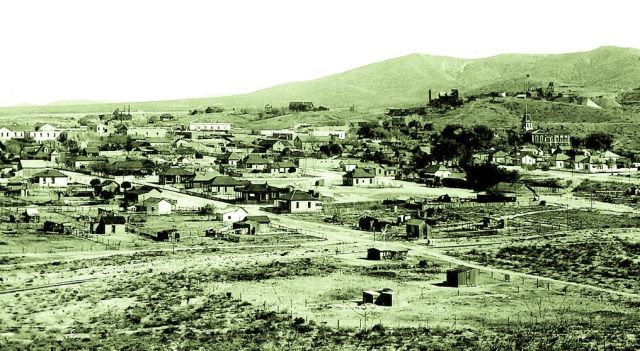

When this birds-eye-view looking south was made about 1911 the population had rebounded to more than 1,500. The photographer set up his camera on the slope of Comstock Hill (a.k.a. “T-Mountain”) on the northwest side of town. At far left is Schieffelin Hall while at right the tower of the Cochise County Courthouse (1882) is visible below the Toughnut mine. Railroad tracks are running across the foreground. The Santa Fe Railway built 1883-1884 from Benson to Fairbank, 12 miles west of Tombstone, and then on to Nogales. It was not until 1903 that a branch of the El Paso & Southwestern Railway reached Tombstone from Fairbank. With new pumps and a railway to ship ore to El Paso, Tombstone’s economy recovered 1903-1908. Then mining became too expensive again. Most of the pumping machinery failed in 1909 and had to be replaced. The new pumps were removing 6.8 million gallons a day by the end of 1910, but Tombstone Consolidated Mines had to borrow $6 million dollars to continue operation in 1911. The numbers didn’t add up. The pumps were abandoned 19 January 1911 and the mine allowed to flood. Ore extraction continued on a smaller scale above the water table until the Great Depression nearly turned Tombstone into a ghost town.

When this birds-eye-view looking south was made about 1911 the population had rebounded to more than 1,500. The photographer set up his camera on the slope of Comstock Hill (a.k.a. “T-Mountain”) on the northwest side of town. At far left is Schieffelin Hall while at right the tower of the Cochise County Courthouse (1882) is visible below the Toughnut mine. Railroad tracks are running across the foreground. The Santa Fe Railway built 1883-1884 from Benson to Fairbank, 12 miles west of Tombstone, and then on to Nogales. It was not until 1903 that a branch of the El Paso & Southwestern Railway reached Tombstone from Fairbank. With new pumps and a railway to ship ore to El Paso, Tombstone’s economy recovered 1903-1908. Then mining became too expensive again. Most of the pumping machinery failed in 1909 and had to be replaced. The new pumps were removing 6.8 million gallons a day by the end of 1910, but Tombstone Consolidated Mines had to borrow $6 million dollars to continue operation in 1911. The numbers didn’t add up. The pumps were abandoned 19 January 1911 and the mine allowed to flood. Ore extraction continued on a smaller scale above the water table until the Great Depression nearly turned Tombstone into a ghost town.

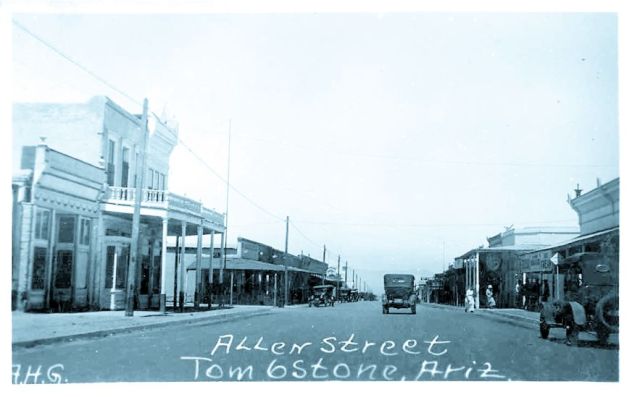

Stores were still open on Allen Street in this photo from about 1915. While many residents hoped for a resurgence of mining, they also promoted tourism. The intersection pictured is Allen at Fifth Street, looking northwest. At this time Allen Street was the main route through town and would carry Highway 80 by the late 1920s. Much later Fremont Street would become Highway 80. The Crystal Palace Saloon (1882) and the former Oriental Saloon (1880), then Tombstone Drug Store, are on the corners at right. At left, on the southeast corner of Fifth and Allen, is a hotel in a building built in 1881 for J. Meyer & Brothers Clothing store and the Huachuca Water Company. Later it was home to the Bucket of Blood Saloon. The building was remodeled in 1909 to become a hotel. It housed the Owl Café (next door; Paul Hood, manager) and Tourist Hotel (Joe Hood, manager) beginning in 1928 but burned in 1942. It is now the site of Longhorn Restaurant.

Stores were still open on Allen Street in this photo from about 1915. While many residents hoped for a resurgence of mining, they also promoted tourism. The intersection pictured is Allen at Fifth Street, looking northwest. At this time Allen Street was the main route through town and would carry Highway 80 by the late 1920s. Much later Fremont Street would become Highway 80. The Crystal Palace Saloon (1882) and the former Oriental Saloon (1880), then Tombstone Drug Store, are on the corners at right. At left, on the southeast corner of Fifth and Allen, is a hotel in a building built in 1881 for J. Meyer & Brothers Clothing store and the Huachuca Water Company. Later it was home to the Bucket of Blood Saloon. The building was remodeled in 1909 to become a hotel. It housed the Owl Café (next door; Paul Hood, manager) and Tourist Hotel (Joe Hood, manager) beginning in 1928 but burned in 1942. It is now the site of Longhorn Restaurant.

In 1928 William M. “Billy” Breakenridge (1846-1931) published his memoir entitled Helldorado, The True Story of Tombstone. The following year “Helldorado Days,” a four-day celebration of gunfights and holdups, prospectors and madams was held in October. But the Great Depression would put a damper on festivities, especially since Tombstone lost the county seat in 1929, leaving its courthouse vacant by 1931.

By 1930 the millions of dollars dug out of the earth had left town long ago. Mining collapsed and Tombstone suffered a severe decline during the depression years. The dark emptiness lurking at the bottom of this photo of buildings along Fifth Street is called the “Million Dollar Stope,” part of an underground excavation that caved in under the weight of a horse and wagon in 1907, exposing the hollowness underlying Tombstone and its economy. Unlike the mine, both horse and driver survived the fall. Nellie Cashman’s Russ House is behind the trees at left and the Crystal Palace Saloon is visible at right. The illustration is cropped from a 1930s postcard by Burton Frasher (1888-1955) of Pomona, California.

By 1930 the millions of dollars dug out of the earth had left town long ago. Mining collapsed and Tombstone suffered a severe decline during the depression years. The dark emptiness lurking at the bottom of this photo of buildings along Fifth Street is called the “Million Dollar Stope,” part of an underground excavation that caved in under the weight of a horse and wagon in 1907, exposing the hollowness underlying Tombstone and its economy. Unlike the mine, both horse and driver survived the fall. Nellie Cashman’s Russ House is behind the trees at left and the Crystal Palace Saloon is visible at right. The illustration is cropped from a 1930s postcard by Burton Frasher (1888-1955) of Pomona, California.

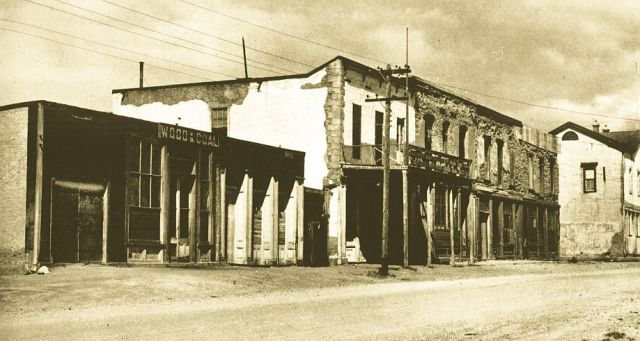

Miners Exchange Hall, also known as the Gird Block (1880) on the northwest corner of Fourth and Fremont Streets once accommodated sessions of the First Judicial District court. Later it became the Hotel Nobles as pictured above behind the Modoc Stage. The corner of Schieffelin Hall is visible at far right. The white-plastered building is the original home of the Tombstone Epitaph. Editor John P. Clum (1851-1932) and two partners printed the first issue dated 1 May 1880. Clum was a Republican, elected Mayor in 1881 and then defeated for re-election the following year after supporting the Earps. May 1, 1882 he sold the Epitaph and left town. The “Wood & Coal” building once housed a public library. The entire row of buildings was demolished in the 1950s and is now a vacant lot. Long before that, the Epitaph relocated to a building just north of the Crystal Palace Saloon on Fifth Street, with the so-called “hangman tree” out front.

Miners Exchange Hall, also known as the Gird Block (1880) on the northwest corner of Fourth and Fremont Streets once accommodated sessions of the First Judicial District court. Later it became the Hotel Nobles as pictured above behind the Modoc Stage. The corner of Schieffelin Hall is visible at far right. The white-plastered building is the original home of the Tombstone Epitaph. Editor John P. Clum (1851-1932) and two partners printed the first issue dated 1 May 1880. Clum was a Republican, elected Mayor in 1881 and then defeated for re-election the following year after supporting the Earps. May 1, 1882 he sold the Epitaph and left town. The “Wood & Coal” building once housed a public library. The entire row of buildings was demolished in the 1950s and is now a vacant lot. Long before that, the Epitaph relocated to a building just north of the Crystal Palace Saloon on Fifth Street, with the so-called “hangman tree” out front.

A rough and tumble mining camp had to have at least one angel and Tombstone had Nellie Cashman (1845-1925). She took in boarders at the Russ House on the northwest corner of Toughnut and Fifth Streets (at right). She saw that the hungry were fed and the sick nursed. And she boldly tore down bleachers erected for a public hanging in order to put a damper on the spectacle. The million-dollar Cochise County Courthouse (1882) is two blocks farther down Toughnut Street (at left). Voters moved the county seat to Bisbee in 1929. The old courthouse became one of the first Arizona State Parks in 1959. In front of the courthouse is an old hospital building (with covered sidewalk). Like most mining towns, Tombstone always had a hospital until recent times. An earlier hospital building was located at the west end of Allen Street. This view of Toughnut Street looking northwest is cropped from a Burton Frasher postcard issued about 1940.

A rough and tumble mining camp had to have at least one angel and Tombstone had Nellie Cashman (1845-1925). She took in boarders at the Russ House on the northwest corner of Toughnut and Fifth Streets (at right). She saw that the hungry were fed and the sick nursed. And she boldly tore down bleachers erected for a public hanging in order to put a damper on the spectacle. The million-dollar Cochise County Courthouse (1882) is two blocks farther down Toughnut Street (at left). Voters moved the county seat to Bisbee in 1929. The old courthouse became one of the first Arizona State Parks in 1959. In front of the courthouse is an old hospital building (with covered sidewalk). Like most mining towns, Tombstone always had a hospital until recent times. An earlier hospital building was located at the west end of Allen Street. This view of Toughnut Street looking northwest is cropped from a Burton Frasher postcard issued about 1940.

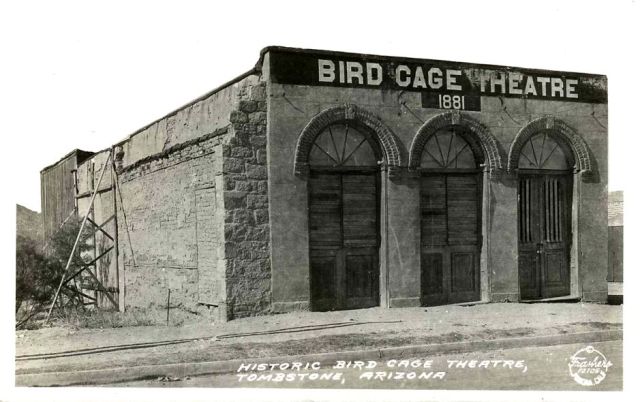

Soon after opening Christmas Day 1881, The Elite Theatre offered men everything that was wild and wicked, and typical of mining boom towns in the West. It was a theater and saloon, with 24-hour drinking and gambling, plus shady ladies for hire. At some point the name was changed to the Bird Cage. It closed in 1925 and by the early thirties when Burton Frasher took this photograph had been boarded up for years. By 1937, visitors could tour the musty interior filled with curiosities. A tiny addition replaced the shoring holding up the wall at left to offer food and drink.

Soon after opening Christmas Day 1881, The Elite Theatre offered men everything that was wild and wicked, and typical of mining boom towns in the West. It was a theater and saloon, with 24-hour drinking and gambling, plus shady ladies for hire. At some point the name was changed to the Bird Cage. It closed in 1925 and by the early thirties when Burton Frasher took this photograph had been boarded up for years. By 1937, visitors could tour the musty interior filled with curiosities. A tiny addition replaced the shoring holding up the wall at left to offer food and drink.

The Oriental Saloon opened 22 July 1881 on the northeast corner of Fifth and Allen, across the street from the Eagle Brewery (later Crystal Palace). Wyatt Earp purchased an interest in the saloon’s gambling tables, some of the most lucrative in town. Where money and liquor mixed, violence followed and several notorious shootings occurred just outside the Oriental. It burned in the 1881 fire but was quickly rebuilt and suffered only minor damage during the fire of 1882. Eventually, the law caught up with the place. After the state legislature enacted prohibition of alcohol in 1914, Tombstone Drug Store moved into the building. Drug store soda fountains were an early alternative to booze. In the 1930s, when Burton Frasher recorded the building in this view, it was advertising cigars, cigarettes, Coca-Cola and ice cream. The post office was housed in the corner of the building at right and the Chamber of Commerce was inside the next building to the right.

The Oriental Saloon opened 22 July 1881 on the northeast corner of Fifth and Allen, across the street from the Eagle Brewery (later Crystal Palace). Wyatt Earp purchased an interest in the saloon’s gambling tables, some of the most lucrative in town. Where money and liquor mixed, violence followed and several notorious shootings occurred just outside the Oriental. It burned in the 1881 fire but was quickly rebuilt and suffered only minor damage during the fire of 1882. Eventually, the law caught up with the place. After the state legislature enacted prohibition of alcohol in 1914, Tombstone Drug Store moved into the building. Drug store soda fountains were an early alternative to booze. In the 1930s, when Burton Frasher recorded the building in this view, it was advertising cigars, cigarettes, Coca-Cola and ice cream. The post office was housed in the corner of the building at right and the Chamber of Commerce was inside the next building to the right.

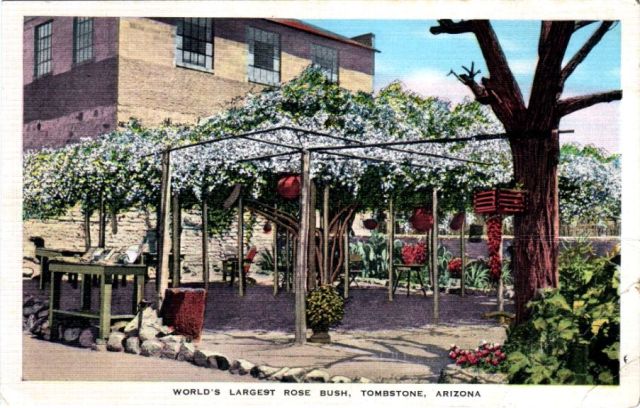

Vizina Mining Company built the first adobe building in town in 1885, a boarding house for employees on Toughnut Street across from the later site of the railroad depot. The same year a rose bush from Scotland was planted in the backyard by Mary Gee. Later, the establishment became the Cochise House Hotel, then the Arcade Hotel from 1909 to 1936. By the 1930s, when this postcard was created, the rose had grown to shade the entire patio out back and was a popular site for tourists. The hotel was renamed Rose Tree Inn. By 1973 the white rambler Lady Banksia variety had spread to cover more than 7,000 square feet with a trunk approaching 60-inches in girth. This past April it bloomed for the 127th time. In this scene the Inn is out of view at right. The two-story building behind the patio is now home to Arlene’s gallery on Allen Street.

Vizina Mining Company built the first adobe building in town in 1885, a boarding house for employees on Toughnut Street across from the later site of the railroad depot. The same year a rose bush from Scotland was planted in the backyard by Mary Gee. Later, the establishment became the Cochise House Hotel, then the Arcade Hotel from 1909 to 1936. By the 1930s, when this postcard was created, the rose had grown to shade the entire patio out back and was a popular site for tourists. The hotel was renamed Rose Tree Inn. By 1973 the white rambler Lady Banksia variety had spread to cover more than 7,000 square feet with a trunk approaching 60-inches in girth. This past April it bloomed for the 127th time. In this scene the Inn is out of view at right. The two-story building behind the patio is now home to Arlene’s gallery on Allen Street.

The Cochise County Hospital opened in Tombstone in the 1880s but moved to Douglas about 1909. In 1945 Dr. Peter Paul Zinn of Bisbee and Father Aloysius “Roger” Aull (ca1895-1948) of New Mexico opened a lung disease clinic known as the Medical Center in an 1881 bank building. Drawing hundreds of invalids from far away, it was soon renamed Tombstone General Hospital. But the treatment did not prove effective and the institution was short lived. The town “too tough to die” benefited more from a number of movies and two long-running TV series: Tombstone Territory (1957-1960) and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp (1955–1961).

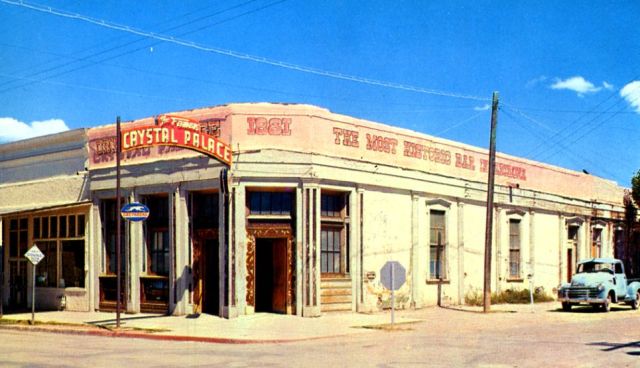

Golden Eagle Brewery (1879-1881) originally occupied the site of the Crystal Palace Saloon. The brewery burned twice then was rebuilt in 1882 as the two-story Crystal Palace. The second floor was removed during a 1904 remodel and then the front arcade over the sidewalk was removed in the 1930s. This view in the 1950s is from a postcard issued by Bob Petley. The next building at left used to be A. Cristini’s grocery 1920s-1940s. The Tombstone Epitaph building is behind the pickup at right. The Crystal Palace has now been restored to two stories with a covered sidewalk once again.

Golden Eagle Brewery (1879-1881) originally occupied the site of the Crystal Palace Saloon. The brewery burned twice then was rebuilt in 1882 as the two-story Crystal Palace. The second floor was removed during a 1904 remodel and then the front arcade over the sidewalk was removed in the 1930s. This view in the 1950s is from a postcard issued by Bob Petley. The next building at left used to be A. Cristini’s grocery 1920s-1940s. The Tombstone Epitaph building is behind the pickup at right. The Crystal Palace has now been restored to two stories with a covered sidewalk once again.

The term “Boot Hill,” for the final resting place of those who “died with their boots on,” probably originated in Dodge City, Kansas. Tombstone’s Boot Hill, used 1879-1884, fell into neglect after it was replaced by a cemetery just beyond the west end of Allen Street. But in an effort to make Boot Hill a tourist destination, ten years of cleanup and restoration 1923-1933 culminated in a billboard along Highway 80. At first the cemetery was thought to be a potters field for outlaws, but then the first non-villain grave was identified in 1937. Local boosters decided a respected businessman, Quong Kee (1851-1938), owner of the popular Can Can Restaurant on the corner of Fourth and Allen, should be given a widely publicized burial at Boot Hill in 1938. The event marked a turning point, away from obscurity and shame for the graveyard, making it one of the most visited sights in town. A custodian was hired in 1945 and he opened a souvenir stand at the entrance. This Kodachrome postcard was issued in 1951 by Curteich of Chicago and distributed by Lollesgard Specialty Company of Tucson and Phoenix. The two iron crosses (at left and by the car) are actually street lampposts moved from downtown. Roy Fourr Post No. 24 of the American Legion placed the stone obelisk in 1937 in memory of unidentified veterans, pioneers and settlers. The graves of OK Corral victims are prominent in the foreground.

The term “Boot Hill,” for the final resting place of those who “died with their boots on,” probably originated in Dodge City, Kansas. Tombstone’s Boot Hill, used 1879-1884, fell into neglect after it was replaced by a cemetery just beyond the west end of Allen Street. But in an effort to make Boot Hill a tourist destination, ten years of cleanup and restoration 1923-1933 culminated in a billboard along Highway 80. At first the cemetery was thought to be a potters field for outlaws, but then the first non-villain grave was identified in 1937. Local boosters decided a respected businessman, Quong Kee (1851-1938), owner of the popular Can Can Restaurant on the corner of Fourth and Allen, should be given a widely publicized burial at Boot Hill in 1938. The event marked a turning point, away from obscurity and shame for the graveyard, making it one of the most visited sights in town. A custodian was hired in 1945 and he opened a souvenir stand at the entrance. This Kodachrome postcard was issued in 1951 by Curteich of Chicago and distributed by Lollesgard Specialty Company of Tucson and Phoenix. The two iron crosses (at left and by the car) are actually street lampposts moved from downtown. Roy Fourr Post No. 24 of the American Legion placed the stone obelisk in 1937 in memory of unidentified veterans, pioneers and settlers. The graves of OK Corral victims are prominent in the foreground.

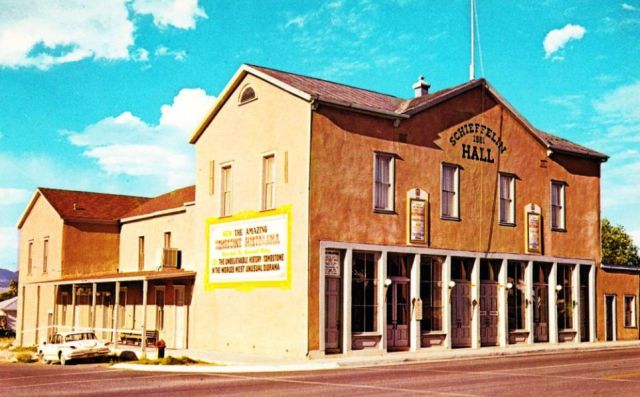

In 1881, Al Scheiffelin (1849-1885) built one of the largest adobe buildings in the entire country as an opera house on the northeast corner of Fourth and Fremont Streets. Every sizable town in Arizona Territory had its “opera house” where all sorts of live shows were performed by traveling companies. Scheiffelin Hall also accommodated meetings of the Ancient Order of United Workmen and the Masons. The Dick Parrish photo was published about 1966 as a Plastichrome postcard by Petley Studios of Phoenix. At that time visitors could see the “Amazing Tombstone Historama” (yellow-bordered sign) in the auditorium, an animated diorama illustrating the town’s history with narration by Vincent Price.

In 1881, Al Scheiffelin (1849-1885) built one of the largest adobe buildings in the entire country as an opera house on the northeast corner of Fourth and Fremont Streets. Every sizable town in Arizona Territory had its “opera house” where all sorts of live shows were performed by traveling companies. Scheiffelin Hall also accommodated meetings of the Ancient Order of United Workmen and the Masons. The Dick Parrish photo was published about 1966 as a Plastichrome postcard by Petley Studios of Phoenix. At that time visitors could see the “Amazing Tombstone Historama” (yellow-bordered sign) in the auditorium, an animated diorama illustrating the town’s history with narration by Vincent Price.

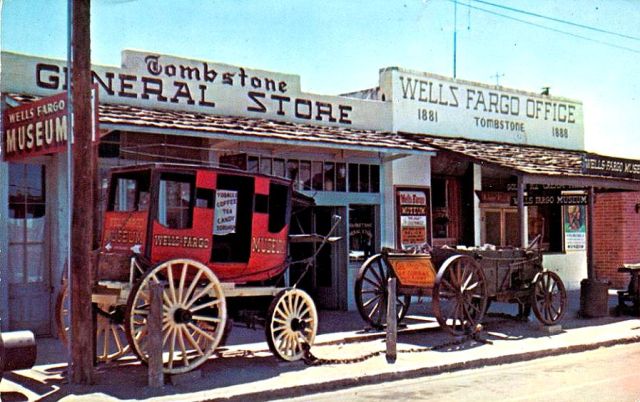

Wells Fargo established its first office in Tombstone in May 1880 near Third and Fremont Streets. The building pictured here is located on Allen Street between Fifth and Sixth. Tombstone General Store had “the old-time fixtures, selling old-time candies and other confections.” The photo by Dick Parrish was published by Petley Studios of Phoenix and printed as a postcard by Dexter Press, West Nyack, New York. It was postmarked in 1969.

Wells Fargo established its first office in Tombstone in May 1880 near Third and Fremont Streets. The building pictured here is located on Allen Street between Fifth and Sixth. Tombstone General Store had “the old-time fixtures, selling old-time candies and other confections.” The photo by Dick Parrish was published by Petley Studios of Phoenix and printed as a postcard by Dexter Press, West Nyack, New York. It was postmarked in 1969.

In recent years Tombstone has continued to ride a series of booms that soon fade. The last train left town 13 August 1960 and the rails were removed soon after. The former depot became the town’s public library in 1961. Highway 80 has lost most of its traffic to Interstate 10. Two recent attempts to mine at Tombstone ended in bankruptcy, in 1985 (Tombstone Exploration Inc.) and 1990 (Cowichan Resources). Nevertheless, release of the movies Tombstone (1993) and Wyatt Earp (1994) brought a new influx of visitors and now the downtown resembles a movie lot theme park. Old buildings have been restored to their 1880s grandeur with bright colors and lots of polish.

See:

Leo M. Banks, “This Shooting at the O.K. Corral Failed to Make the History Books,” Arizona Highways, Oct. 1998, pp. 22-25

John A. Black, Arizona, The Land of Sunshine and Silver, Health and Prosperity, The Place For Ideal Homes, (1890)

T. Roger Blythe, A Pictorial Souvenir and Historical Sketch of Tombstone Arizona, (1946)

William M. Breakenridge, Helldorado: The True Story of Tombstone, (1928)

Kevin Britz, “‘Boot Hill Burlesque’: The Frontier Cemetery as Tourist Attraction in Tombtone, Arizona and Dodge City, Kansas,” The Journal of Arizona History, Autumn 2003

B. S. Butler, et al., Geology and Ore Deposits of the Tombstone District, Arizona, U. Of A., Arizona Bureau of Mines Bulletin 143, (1938)

Eric L. Clements, After the Boom In Tombstone and Jerome. . ., (2003)

Stephen Cresswell, Mormons & Cowboys, Moonshiners & Klansmen: Federal Law Enforcement in the South & West, 1870-1893, (1991)

Jane Eppinga, Arizona Sheriffs, (2006)

Jane Eppinga, Around Tombstone, (2009)

Jane Eppinga, Tombstone, (2010)

Douglas D. Martin, Tombstone’s Epitaph, (1951)

Douglas D. Martin, “Tombstone’s Epitaph,” Arizona Highways, Sept. 1951, pp. 2-9

Joseph Miller, “Tombstone, ‘The Town Too Tough To Die,’” Arizona Highways, May 1945, pp. 32-37

Sherry Monahan, Taste of Tombstone, (2008)

Sherry Monahan, Tombstone’s Treasure, (2007)

Joseph P. Schwieterman, When the Railroad Leaves Town, (2004)

James E. & Barbara H. Sherman, Ghost Towns of Arizona, (1969)

Stewart L. Udall, The Forgotten Founders, (2002)

W. John “Jack” Way, The Tombstone Story, (1965)